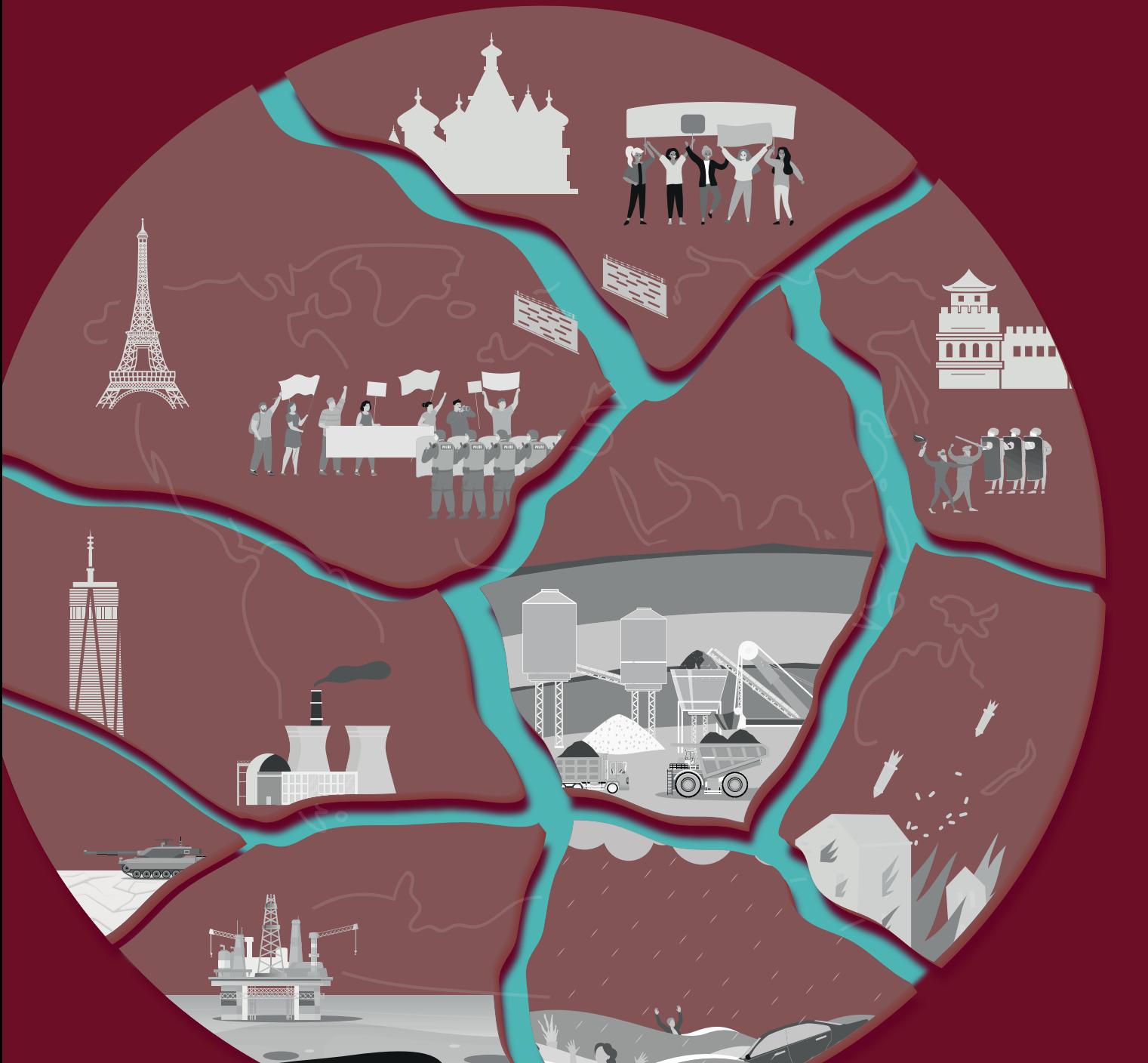

Downward Spiral

Countries fall into a regressive trap in pursuit of total self-sufficiency

Rampant resource nationalism has diminished international trade and cooperation as countries turn inward to achieve self-sufficiency across energy, water, food, and raw materials production. However, the results are economically regressive and socially divisive. Restrictive policies breed constant volatility and hamper progress on issues that require shared interests like environmental standards and climate resilience, while governance capture by nationalist lobbies fosters unrest, crises of legitimacy, and active conflicts. As a result, sustainability has taken a back seat to cost considerations, ultimately culminating in widespread environmental degradation, widespread vulnerability to climate change, and policy opposition to challenging stabilization measures.

Key aspects

Rampant resource nationalism has led countries to turn inward and pursue self-sufficiency across supply chains. This regression breeds economic volatility, social divisions, and a deterioration of shared interests like environmental protection and climate resilience. To maintain control, regimes invoke nativist identities to justify crackdowns on dissent. Constantly shifting opportunistic policies foster corruption and repeated crises of legitimacy, and international cooperation and universal rights are framed as subversive ideals.

Resource-driven conflicts between major powers sparked several regional wars. Economic, political, social, religious, and cultural divides make prospects of global peace and cooperation remote. Infrastructure suffers from depressed investment and inefficient duplication across countries, severely hampering productivity. National and regional markets, prone to exaggerated demand-supply imbalances from waves of protectionism, experience extreme volatility. The resulting downturns and upcycles devastated communities and created economic distribution that fueled inequality and social unrest.

International Cooperation and Domestic Policies

- Restrictive policies hamper progress on shared interests like peacekeeping and climate resilience. Most international institutions have lost their influence and are nonfunctioning.

- Nationalist economic policies prioritise domestic self-sufficiency over global trade and cooperation. Countries vie to control entire supply chains within their borders, enacting export restrictions and barriers to international collaboration.

- The exit of foreign investors and retaliatory import taxes damage national economies, creating political turmoil and government instability across several nations, though new governments across the world persist with such inward-looking approaches.

Economic Situation

- Nativist policies exclude critical foreign investors leading to halted upgrades and maintenance of existing infrastructure, limiting longterm extraction, processing, and export capabilities across industries.

- Protectionist measures result in below-average global GDP growth as countries deviate from leveraging comparative advantages and engaging in efficient trade.

- The mining sector provides below-market capital returns due to falling domestic prices driven by slow economic growth.

- Resource nationalism drives exorbitant royalty rates and taxes and periodic nationalization creating unsustainable risk premiums and deterring investors.

Society and Environmental Aspects

- Economic crises and authoritarian crackdowns spark civil clashes, violent ideological extremism, and waves of mass migration - overwhelming remaining governance capacities. In some regions, security forces unable to maintain order give way to warlordism and paramilitary rule.

- Environmental degradation is the norm as nationalist regimes dismantled oversight bodies and suppressed activism in the race for industrial self-sufficiency.

- Oversupply within domestic markets forces mining companies to sell products at lower prices, prompting cost-cutting measures that weaken environmental and social practices, souring public opinion on mining.

- Mining firms focus on water and energy conservation due to environmental concerns and resource limitations, choosing efficiency over innovation to address the growing risks associated with water and energy supply.

- The few remaining progressive regimes retreat to climate-fortified borders, unable to mobilise regional or global cooperation on climate resilience or adaptation. All signs pointed to cascading system collapse.

The Mining Value Chain and Mining Technologies

- Regulators weaken oversight to incentivise domestic mining, concentrating environmental damage domestically which prompts battles over clean air and water in mining regions.

- Companies concerned with risk mitigation focus on efficiency improvements and maximising returns, often bypassing innovative technologies unless prompted by governments.

- Depending on risk appetite and state funding support, mining firms either seek vertical integration or outsourced activities to more riskaverse specialised players.

- Material science and mining, processing, and recycling technologies advance in some areas to improve efficiency, but trade barriers and missing global supply chains curb potential impacts on productivity.

- Unstable commodity prices, along with climbing taxes and royalty rates from resource nationalism, hamper investments in new projects and further dissuade investors.

International Cooperation and Domestic Policies

International Cooperation and Trade

Rampant resource nationalism drives most nations to severely restrict international trade and cooperation in pursuit of economic self-sufficiency. International institutions have been hollowed out and became nonfunctional as countries prioritised narrow national interests. Global issues like peacekeeping operations, tackling climate change effects, and environmental conservation are largely abandoned in the absence of international cooperation.

Ad hoc, opportunistic alliances form between nations when short-term economic or security interests align, but these partnerships are strictly transactional and dissolve regularly with shifting political winds. The global community is fractured, and dominant military and economic powers impose their spheres of influence and arbitrary rules and standards on weaker countries.

Global institutions exist to maintain a basic level of needed coexistence and communication. Diplomacy is limited to serve nationalist agendas. Historical political and ethnic grievances spark conflicts and economic wars over resources and regional dominance. With no neutral arbiters or mediating institutions left, these conflicts exacerbate global instability.

Government Regulation and Stability of Domestic Policies

The inward economic policies implemented by most nations, like bans on exports and raw materials, punitive tariffs, and expropriation of foreign-owned industries, have backfired severely and caused intense domestic instability. While intended to capture entire supply chains domestically, these restrictive practices deter foreign investment in local infrastructure and industry. The ensuing access to limited capital creates chronic shortages and rationing. Uncertainty and xenophobia prompt remaining global firms to divest or scale down operations further in many countries, resulting in depressed productivity and technological stagnation.

Incumbent regimes have lost public faith as living standards plummet amid inflation, job losses, and shortages of critical imported goods like food, energy, and medicines. Attempts to expand domestic production capacity cannot offset vulnerabilities, as homegrown industries lack scale and reinforcements from global supply chains and trade partnerships. This fuels public dissent and a pattern of mass protests, violent government crackdowns, power seizures by authoritarian extremists, and further economic headwinds.

Economic Situation

Infrastructure

The flight of foreign investment severely constrains countries' future growth prospects. Reduced economic activity in the mining sector translates to a downward spiral with supply constraints and deteriorating infrastructure, leading to major losses of government revenues, jobs, and critical infrastructure investments. Risk-averse investors refrain from new projects and halt or cancel upgrades and maintenance to existing infrastructure. This creates a downward spiral of poor infrastructure leading to lower productivity, which further disincentivises infrastructure spending. Over the long term, severely degraded transport, power, and internet connectivity bottlenecks hamper the overall economic production capacity and export across sectors. The impact is most acute in developing countries where the extractive sector accounts for a sizable share of GDP and has multiplier effects across supply chains.

Economic Development

The wave of protectionism and the deterioration of global supply chains multiplied inefficiencies for all countries as they contorted economies to achieve self-sufficiency. Rather than focusing efforts on comparative advantages, specialisation, and mutually beneficial trade, countries expend far more resources domestically producing goods at a competitive disadvantage. This drags down both short- and long-term economic growth trajectories. Most countries' real incomes stagnate or decline over decades. The loss of economic complexity also makes countries more vulnerable to global commodity price volatility.

Price Volatility

Erratic policy shifts cause wild price swings for resources and materials within countries over short periods, creating economic chaos. Export bans initially flooded domestic markets with minerals, metals, and other commodities, depressing prices as homegrown processing capacity is limited. In response, miners throttle production, setting up the next supply crunch when export bans shift again. Countries that restrict exports of key inputs see drastic price spikes and shortages for domestic manufacturers. These violent boom-bust cycles handicap businesses, disrupt supply chains, and hammer household budgets and the socio-economic fabric.

Profit

Unstable and plummeting commodity prices combine with creeping resource nationalism to severely impact mining profitability. Governments seek higher shares of mining revenue through increased royalties, taxes, and threats of expropriation to close growing budget gaps. This toxic policy climate disincentivises investors seeking market-rate returns, deplete capital for new projects and technology upgrades, and drag the entire sector into a long-term productivity decline relative to the overall economy. The extractive industry became synonymous with country risk and confiscatory regimes. Only the most risk-tolerant investors remain active in the space.

Society and Environmental Aspects

Responsible Consumption and Production & Social Attitude towards Mining, Public Acceptance

The public soured on the mining industry as the negative impacts of unchecked extraction piled up within countries pursuing self-sufficiency. With export markets closed, miners flood domestic commodity markets, depressing prices below profitability levels. Many cut costs by rolling back environmental and community investments and abandoned social license efforts. Health and pollution externalities are passed on to the public as oversight has faded. After experiencing first-hand the abusive practices enabled by resource nationalism, public attitudes towards mining worsen markedly over time despite initial nationalist-driven fervour.

Integrated Climate Action

Domestic mining policies oppose widescale changes that would transform carbon-intensive conventional practices, instead only permitting incremental efficiency improvements that result a status quo reliance on fossil fuels. Without concerted climate policies or international collaboration driving demand for low-carbon minerals, most mining does little to enable the energy transition. Renewables and electric vehicles remain niche. While miners make some site-level adaptations to climate risks in vulnerable regions, they play no role in developing mitigation or carbon removal technologies at scale.

Water and Energy Strategies

With mining productivity and recycling practices handicapped by economic policies, most companies retrenched around low risk conventional deposits. Exposure to water stress and energy poverty increased. Periodic shutdowns or output cuts became commonplace as local community needs clashed with industrial usage. Most adaptation measures focused on improving efficiency and conservation driven by cost control rather than systemic resilience to intensifying climate impacts. Even major investments couldn't offset the underlying vulnerability of mining operations in water-scarce, energy-poor regions once considered fringe. Supply disruptions from climate disasters became common.

Environmental Impact of Mining

Government incentives around raw materials production cluster extraction and processing geographically, overburdening particular communities to achieve domestic self-sufficiency aims. Remote and mineral-rich areas see environmental standards weakened to support needed industrial growth. Some domestic clusters of mines and recycling centres benefit from government support for infrastructure, processing hubs, specialised services, and captured economies of scale. However, these clusters also result in pollution accumulating to extreme levels with little recourse for local communities suffering health effects and loss of traditional livelihoods. With oversight gutted everywhere, environmental disasters occur more frequently, even in developed regions.

The Mining Value Chain and Mining Technologies

Market Demand for Raw Materials

Ongoing global economic weakness and extreme commodity price volatility depresses demand for raw materials. Existing miners and recyclers focus on cost-cutting and operational efficiency rather than expanding production or investing in new capacity. Many high-cost mines are shuttered, removing their supply and potential capital from the economy. Material intensity per GDP stalls worldwide. Modest growth remains confined to developing countries and regions tapping local mineral resources out of necessity to fuel industrial self-sufficiency drives, though output lags badly on costs. Clean energy remains a niche without climate policies. Extraction activity contracts overall from peak levels.

Industry Structure and Value Chain Structure

Many miners pursue vertical integration into domestic transportation, processing, and manufacturing to bypass export barriers. But with only localised end-markets, overinvestment and underproduction is common and periodically supported by government subsidies to ensure basic sourcing. When self-sufficiency policies fail to deliver expected demand growth, low commodity prices make these capital-intensive facilities unprofitable. Shareholder pressure pushes majors to focus on efficient mining while offloading processing assets to specialised domestic firms better equipped to handle market volatility in smaller niches. The rise of flexible niche players offsets tendencies toward complete vertical integration.

Exploration, Share of Mining in Extreme Conditions, and Extraction Technologies

Developed and developing countries follow different paths around mining productivity. Advanced economies leverage technologies like AI, remote operation, remote sensing, and automation to unlock new deposits and sustain output despite high costs. Their expertise allows economic access to ever more extreme locations previously out of reach. Poorer but resource-rich countries remained trapped, relying on cheap labour with only incremental innovations available locally. Extraction technologies have bifurcated, based on national capabilities and government support.

R&D

To bypass reliance on imports, governments fund basic research into substituting imported critical raw materials across defence, technology, and manufacturing applications with accessible materials. However, depressed economic conditions ensure only minimal resources redirected from immediate needs, and the lack of international collaboration causes duplication of effort. Technology advancements slow below their potential, handicapping industrial development.

Winners and Losers

Winners

Industry

- Risk-averse, internally well-capitalized mining companies (sometimes with government backing) willing to invest in rich countries and vertically integrating (or willing to provide specialized services in the form of infrastructure investments or processing plants).

- Companies with capacity to leverage advanced exploration and mining techniques.

- Domestic mining and processing companies that align interests with ruling regimes.

- Black market smugglers and illegal mining networks dealing in materials scarce in domestic markets.

Regions, Organizations, and others

- Resource-rich countries (short-term).

- National/Regional financial institutions with very focused and specialised investment goals.

- Authoritarian regimes and nationalist extremists who exploit economic turmoil and social unrest to expand their power.

- Powerful countries with large domestic markets, resources, and advanced technologies to pursue self-sufficiency.

- Private military contractors and security firms that profit from conflicts and instability.

Losers

Industry

Regions, Organizations, and others

- Countries lacking resources or capabilities that can approximate self-sufficiency.

- Countries heavily reliant on trade and global supply chains for economic growth.

- Citizens and local communities impacted by concentrated environmental damage and pollution.

- Marginalised ethnic groups scapegoated for economic troubles.

- International institutions, NGOs, human rights, and environmental activists.

- General public enduring restrictions, shortages, inflation, and depressed real standards of living.

Protagonists

- Technology companies.

- Authoritarian and nationalist governments.

- Powerful, state-owned raw materials producers.

- Black market networks.

- Security services and military forces.

- Insurgent groups and extremist organisations.

Disruptions

Geopolitical

- Collapse in rule of law, allowing criminal networks to overwhelm state authorities, and collapse of residual capital flow.

- Radical extremist factions overthrowing nationalist governments.

- Emergence of more liberal internationalist successor generations within closed regimes.

- Significant disruption in major powers leading to external geopolitical realignments.

- Transnational activist cyber-attack crumpling industrial systems infrastructure.

Economic

- Breakthroughs in renewable energy, batteries or carbon capture lowering demand/prices for mined commodities.

- Revolution in materials science lowering needs for contested rare-earth minerals.

- Unforeseen technology innovations (AI, synthetic biology, clean fusion, etc.) disrupting production.

Social

- Mass organised labour strikes or middle-class protests within authoritarian countries.

- Ethnic insurgencies or civil wars inside resource-rich failed states.

- Global pandemic or food system crisis exacerbating migration and instability.

Environmental

- Watershed ecological/climate disaster events spurring emergency cooperation.